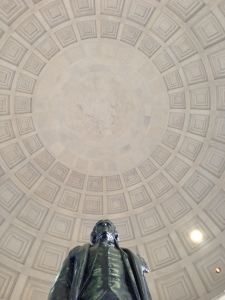

The Jefferson Memorial: a statue of Jefferson, set against the Pantheon-like dome of the memorial pavilion.

“You’ll love D.C. It’s like a celebration of democracy,” Angela,* the woman with whom we shared a taxi into the city, declared with a grin. She was visiting her daughter, who was studying at Georgetown University. “I lived abroad for a number of years, and each time I come back to D.C., I’m reminded of how great it is.”

The taxi driver also joined the conversation, telling us about his experiences as an immigrant in the U.S., as we approached the National Mall at twilight.

“What a beautiful way to see it for the first time,” Angela exclaimed, as we passed the White House on our way to our hotel.

Over the next several days of our whirlwind tour of the city, others would also tell us how D.C. is a “tribute to democracy”, or even “the center of democracy.”

And yet, the portrait of the city that emerged for me was far more intriguing: it is one of the key narratives through which a nation has chosen to represent itself, to its own people, and to visitors from abroad.

D.C. is a place of Roman or Hellenic aspect, resonant with echoes of the Athenian, democratic city state and the Roman republic of old. The National Mall and its surrounding monuments embody elegant austerity on a vast and grandiose scale. But, most fascinatingly of all, the core of the city, with its monuments and sites, manifests and narrates the mythos that a country has created for itself. Against the backdrop of the vision of a secular nation (even if that secularity seems somewhat elusive these days) and the separation of religion from state, I wondered whether this mythos had been created in order to facilitate a bridging between theology and ideology. It was almost as if at some deep level, the nation-building designers of the city had known that new saints and magnificent, heroic mythologies had to be created in order for people to resonate deeply, and align themselves with the patriotism of the growing nation.

As we walked the precincts of the District of Columbia, I couldn’t evade the impression that the monuments were like shrines along a secular pilgrimage (“…and this was where Lincoln sat–we have recreated the box to look as it would have at the time… afterwards they took him across the street to the house across the way–you can visit there next–and that’s where he breathed his last…”): lives of the saints and narratives of martyrdom and sacrifice to the great father nation–the patriotic cause.

As if to underscore this impression of shrines, mythmaking and canonization, the woman who led our tour of the Capitol told us that they had planned to inter George Washington’s remains under the foundation of the Capitol building itself, a plan which would have transformed the building itself into an old world shrine or mausoleum. The symbolism of it: in his eponymous city, the remains of the first president, interred in the very foundation of the building that symbolizes the democratic state that was to be built upon those foundations, the place in which the government continues to operate. In the end, they hadn’t, because Washington’s will had not aligned with this vision, but in many ways, they might as well have done.

You can spend your entire day–or days–making the pilgrimage from memorial to memorial: Washington, WWII, Korea, Vietnam, Martin Luther King, FDR, Jefferson. Each has been lovingly created, rife with symbolism and depth, evocative of the event, the legacy, the heroism. There are also the sites that supplement and support this mythos: Ford’s Theatre, the National Archive and its display of the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence and other key constating documents of the state. It is a potent homage indeed, as is the presence of the Apollonian structure that houses SCOTUS, and that modern-day Alexandrian library, the wondrous Library of Congress.

The capital city is magnificent. No doubt about that. The stunning monuments, the vast spaces, the Speer-like proportions, and the austere structures, all contribute to a sense of dwelling at the heart of a great and prosperous nation. Where in other parts of the country, once-great cities are fraying into extreme polarizations between the haves and the have-nots, or are unraveling completely into spent, abandoned, decaying spaces, D.C. is keeping up appearances. The story it tells visitors–pilgrims from within the U.S. and beyond its borders–is one of greatness and prosperity, thus creating a fascinating dissonance between these stunning and glorious surfaces, and the realities behind them.

This narrative of ideals, the enshrining of the aspirational dream, serves as a stark contrast to the current state of the nation–and the ways in which those carefully conceived checks and balances, implemented in order to keep the politicians honest and the democracy functional, have been taken to extremes and exploited in support of private agendae. The Capitol, that iconic, domed “center of democracy”, is now also the center of endless filibusters, of government shutdowns, extremes of rhetoric and the passing of laws that have eroded the Bill of Rights into a shadow of its original self.

Indeed, this metaphorical resonance was not lost on me, as we scrutinized the original Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights, reverently housed in the National Archive. Despite all efforts, the writing has faded with time; in some places the words are almost impossible to discern. This is the state of the surviving artefacts: the legacies of the founding fathers’ lofty dreams of democracy.

*I don’t actually remember Angela’s name, so I made this one up.

And like all those other faded cities, there is plenty of poverty, crime, and unpleasantness under the mythic surface of the city of Washington, DC, too.

It’s true, Lorinda! As the tourist, we didn’t see that as much, except in brief glimpses: our hotel was right beside a park, and I was advised that we shouldn’t cut through the park after dark. I was thinking about that and other glimpses (homelessness a block away from the White House and other opulent districts) when I was writing the have/have not stuff.

The National Mall and its environs are impressive and austere–the core of the myth-building–but like so many of those other cities, DC also has its extremes, its underside and its threadbare, fraying edges.